Words: Lavinia Ionescu

Photos: Robert Blaj

July 2024

A UNIQUE JOURNEY / The City and What Lies Hidden from Sight

I open my eyes and look at the city. The city of buildings. The city of roads. The city of urban tumult. The vibrant city where I briskly walk. And, in its immediate vicinity — like an affective portal — the private city that I discover with my other senses. I close my eyes. The city whispers a story to me. It tells me the story of its plants, of their subtle charm. It sends me on a sensitive expedition in pursuit of its botanical beauty. I invite you, dear reader, to embark together on a soulful tour and discover Bucharest differently: the city as a discreet garden, illuminating enigmatic meanings and opening up new sensory paths.

THE CITY OR NATURE / The City and Nature

A specific narrative about the city has taken root. A form of human settlement developed not only horizontally but also vertically, the city is often perceived in the collective imagination as an antithesis to nature. Two narrative poles: the city and nature, the city versus nature. A counter-perspective, which aims to reclaim and restore the city to nature, highlights the plants and the influence they have over it and its inhabitants, yet often on the margins of the urban story. The life of the city is essentially linked to the life of the plants that populate it. Parks, public gardens, greenhouses, and botanical gardens bear witness to the deep connection between the urban space and its inhabitants.

An invaluable resource, green areas within the city help urban environments become livable, sustainable, and functional spaces. Considering that by 2050, seven out of 10 inhabitants of the planet will live in urban environments, the connection between plants and the city becomes even more relevant. Green spaces act as a buffer zone between busy roads and residential areas. They combat noise pollution, help reduce heat waves due to global warming, contribute to the removal of pollutants, and improve air quality. Additionally, they enhance biodiversity and provide habitats for various animal and plant species.

Regarding the connection between plants and humans, numerous studies clarify the multiple physiological and psychological effects of recovery and relaxation. Touching a plant not only provides a sense of comfort but also has a positive influence on the immune system and the nervous system. The smell of plants plays an equally important role: it triggers physiological mechanisms to calm brain activity. We can access experimental studies on how the visual stimulus of nature and plants beneficially reflects in the human mind and body. In the relationship with plants, all our senses are involved.

MY RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CITY / When the Earth Takes on a Playful Form

When I moved to Bucharest more than 20 years ago from a small provincial town near the Bulgarian border, I imagined its boundlessness. Its urban explosion captivated me. I was seduced by its bustle. Wide frames, intimidating boulevards, geometric mountain-like blocks, giant parks – all welcoming me, a young student eager to broaden her universe. So, slowly, decade after decade, year after year, I discovered with tenacity, but also with sensitivity, its nooks, the delight of green hideaways, and the charm, the flavor of open spaces. I learned about a sensitive Bucharest. Green Bucharest – a city of branches and flowers. Of leaves, shadows, colors. Bucharest of clean air. Bucharest of the outdoors.

BUCHAREST AND ITS OVER 50 PARKS / Curved Corners of Blooming Green

Our itinerary begins with opening our senses. We breathe deeply and immerse ourselves in the great city. We entrust ourselves to its unseen and warm hand. It is no longer just a collection of roads, asphalt, buildings, and routes. It is a voice that speaks to us in sweet, whispered tones. And as we explore its urban circuits, it invites us to discover its mysteries. Vast spaces and intervals where green comes to life and nurtures life. Where plants grow, expand, and emanate life.

The Japanese Garden / Cherry Blossoms and Spring Vibes

Our first stop is in April, in the Japanese Garden. When the Japanese cherry blossoms, of an unusual and dizzying pink, invade our senses. When the grass, the colors, the buzz of spring bring a new energy to the earth. We can connect. Anyone who desires a leisurely picnic among the blooming trees can enjoy it here. The garden is located in the southwest part of the largest park in Bucharest, now called King Mihai I of Romania, but still known as Herăstrău Park. Inaugurated in 1936, it covers an area of over 100 ha, 74 of which are occupied by Lake Herăstrău. Nearby, you can also visit the Triumphal Arch, built in the interwar period following the model of the one in Paris, because, yes, Bucharest was once nicknamed “Little Paris.”

Cișmigiu Garden / A Green Oasis in the Heart of Bucharest

Another iconic place in the city is Cișmigiu Garden. Inaugurated in 1854, Cișmigiu Garden is Bucharest’s first urban park, a space where the relationship with greenery is continuously rediscovering itself. A pleasant scent of good weather invites us to stroll along its paths, to let ourselves be carried among the soft, newly emerged branches, to relax under the leafy halo of the centuries-old trees. Here, the city sheds its own weight, becomes flexible, and reveals its gentle, calm, regenerative side.

Over time, over 30,000 trees and other plants have been planted here: linden trees, maples, elms, plane trees, fir trees, and ash trees. Cișmigiu, with its alleys smelling of linden in autumn, is located ultra-centrally, just a few hundred meters from the University of Bucharest. Inside the garden, we can choose the desired activities. An idyllic boat ride on the lake or a game of badminton in the summer. A stroll under the flowering linden trees in the fall. A mulled wine at the Zona Liberă Boutique, in the winter… or in any other season. Letting ourselves be carried away on the green paths, we may come across La Cetate, a place where the ruins of a monastery built in 1756 can be found. Or the chess corner, where seniors gather to socialize when the weather allows.

Izvor Park / An Open Playground and The People’s House

And since we’re right in the center of Bucharest, it would be a shame not to take a quick trip to Izvor Park. Here I played ping pong for the first time. Here I celebrated several outdoor birthdays. Here we came during the pandemic to get some fresh air in scattered groups while maintaining social distance. Sparse trees and shrubs cover the park’s ground, giving us a pleasant feeling of openness. Dogs of all breeds and sizes run freely throughout its expanse. The northern side is flanked by the Palace of Parliament, known as the People’s House. A mammoth building constructed between 1984-1989 at the command of Nicolae Ceaușescu, over the former Uranus neighborhood. It ranks third for the largest administrative building for civilian use by surface area in the world. It is also the world’s most expensive administrative building – and the heaviest building on Earth. The National Museum of Contemporary Art is also housed here to make the image perfectly eccentric. It’s worth a visit. The terrace of the café-community center of the MNAC invites us to enjoy a hot tea and the view from above Bucharest from the 4th floor of this oversized building.

Titan Park / A “Neighborhood” Mellow Park

6 km further to the east, lies IOR Park or Titan Park (currently, Alexandru Ioan Cuza), the second largest park in the city. A “neighborhood” park. Last century, in the post-war period, with industrialization, solutions were sought to accommodate the population coming from rural areas – the workforce for the new factories and plants. Thus, extensive working-class neighborhoods were created starting in the 1960s in Bucharest. These “bedroom neighborhoods,” as they were derogatorily dubbed, were initially small satellite towns of the center, each with a central park nearby, with playgrounds and other recreational areas designed to provide comfort and rest. Here, in the Titan neighborhood, IOR Park, along with the natural lake that surrounds it, remained for decades the green space for the neighborhood’s population and those from neighboring areas.

I think again about this immense resource: the natural environment and its therapeutic power. Numerous studies prove its restorative effect and its ability to reduce stress and mental fatigue prevalent with increasing urbanization. A study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology reports that after 50 minutes of walking in a natural reserve, the anger decreased and positive emotional effects were evoked – non-vigilant attention, restricting negative thoughts and returning autonomic arousal to more moderate levels. The influence of nature therapy is receiving special attention from an epidemiological point of view, and studies demonstrate a connection between the lack of green spaces near residential areas and the incidence of diseases. Exposure to nature seems to have an extraordinary beneficial impact on mood, concentration, physical and mental health of city dwellers.

Văcărești Delta Natural Park / A Story of Nature’s Resilience

A little further south, covering an area of almost 200 ha, is the Văcărești Delta Natural Park – a protected natural area whose ecosystem is in an incredible natural balance. Yes, a small delta, not far from the city center. A small delta between blocks and boulevards, where nature has reclaimed its rights, to the surprise of many. In 1988, in the place where once there was a marshy region, on the outskirts of the old neighborhoods of Bucharest, a large hydro-technical project began: the construction of the Văcărești reservoir lake. The project was to be part of the city’s flood defense network. But with the political events of December 1989 (the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe), industrial works were suspended, and on their ruins, in about a decade, nature reclaimed the territory. Slowly, the perimeter was populated by countless types of plants and animals.

After 2012, when National Geographic dedicated an issue of the magazine to the Văcărești Delta, highlighting the uniqueness and biodiversity of this new ecosystem in the heart of the city, the area caught the attention of the public and of the environmental activists. In 2016, following a meticulous lobbying process and civic mobilization, the government included the Văcărești Natural Park in the list of protected areas. In recent decades, the renatured territory has become a magnificent aquatic ecosystem hosting over 100 species of plants and habitat for numerous species of reptiles, fish, insects, mammals, and over 170 species of birds. According to the Romanian Ornithological Society, Văcărești Delta is the best birdwatching spot in Bucharest. During the spring or autumn migration periods, smaller or larger groups of birds put on exciting shows especially in the early morning, when they are most active. During this period, those interested can also enjoy guided birdwatching tours led by specialists. The park is equipped with paths, trails, and jogging routes where visitors can walk, run, and recreate in the middle of nature.

The Botanical Garden / Timeless Calm and Historic Charm

And because we’re talking about nature, we couldn’t overlook a visit to the Dimitrie Brândză Botanical Garden. Founded in 1860, it had as its first director the renowned botanist Ulrich Hoffmann. After a series of changes, in 1884, under the leadership of Dimitrie Brândză – one of the founders of the Romanian botanical school – the garden found its permanent location in the immediate vicinity of the Cotroceni Palace (the royal residence now serving as the headquarters of the Presidency of Romania).

We enter. Here, somewhat paradoxically, the timeless calm of plant life blends with the historic charm of the buildings on the premises, built specifically for studying and preserving thousands of plant species. The botanical museum, the old greenhouse (with its tropical ambiance), and the new greenhouse are three refuges worth exploring once we’re here. Stepping on the winding paths, a guiding maze opens up to us towards the alchemical power of vegetal fibers. A multitude of shapes, textures, and colors abound around us. I realize – the charm of plants lies not only in their aesthetic beauty but mostly in their resilience, in the gentle power they radiate.

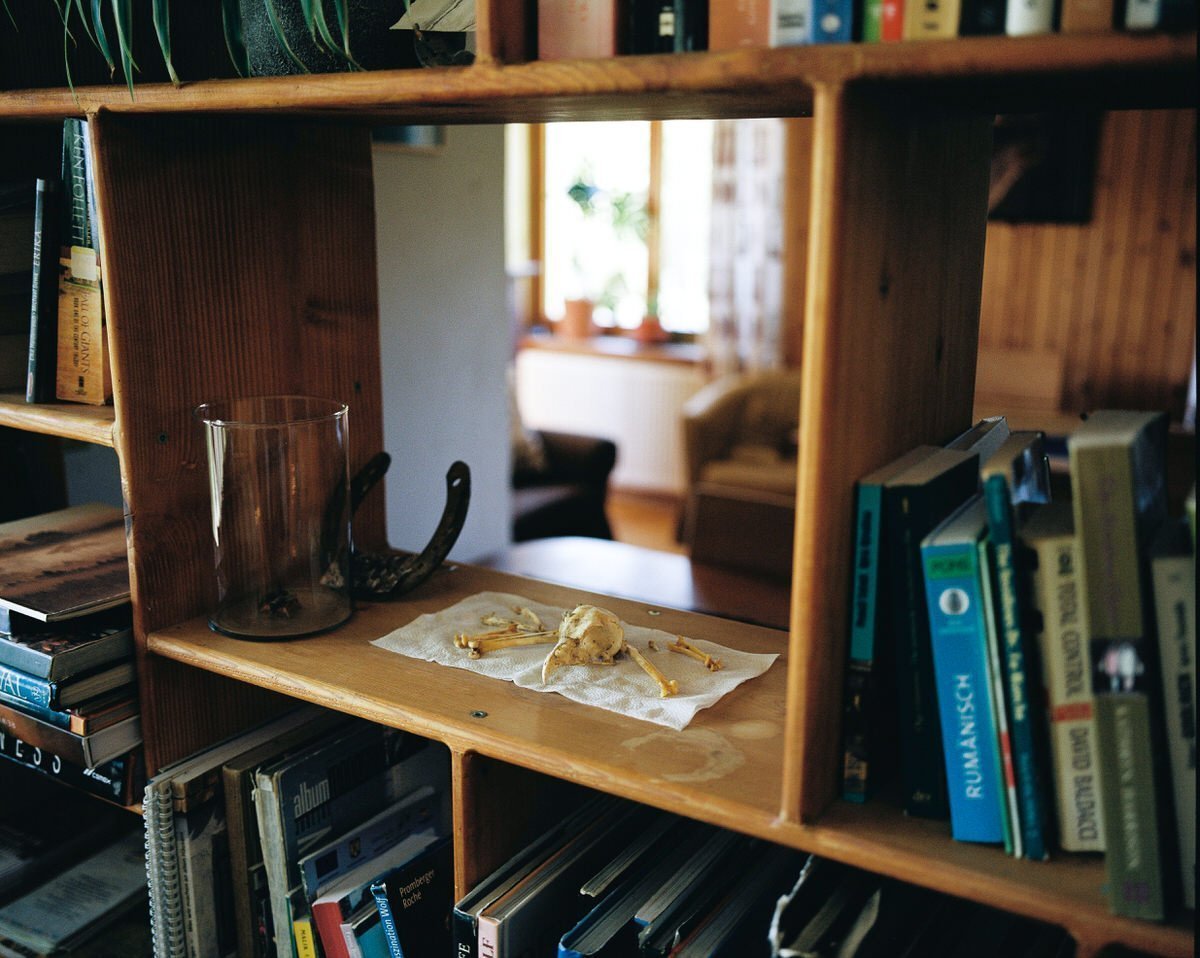

As we continue our walk in the static breeze of a late warm spring day, we reach the Rosarium, one of the ornamental sectors of the garden. Over 200 species and varieties of roses from around the world offer us the magic of their floral beauty. Not far from here, we come across the Historical Garden sector. We discover the territory of “botanical species and varieties consumed throughout European food history,” as presented by Mona Petre, the author of the book Forgotten Herbs and one of the founders of the garden. Here, we find vegetables and other rare spices that are no longer planted today and that once constituted – “before the invasion of New World vegetables” – the usual food of Romanians.

BUCHAREST, CITY OF GARDENS / Green Fortress and Community

If we leave the perimeter of the Botanical Garden and head up towards Militari, one of Bucharest’s neighborhoods, we can see another layer of the city. Anyone who comes to Bucharest and chooses to explore the areas outside the central area is greeted by the steadfast presence of “communist blocks” – entire neighborhoods built to accommodate the workforce from the countryside. Impressive and cold on the surface, bustling and cramped “behind,” the blocks and their surroundings, hidden from the boulevard view, have been a green fortress for their inhabitants over the decades. Once moved to the city, the new tenants did not permanently abandon the practices of courtyard life, reformulating them for life and conditions in the blocks. As we learn from a more detailed study of the city’s community gardens, Bucharest has always been a city of gardens: “utility or aesthetic, i.e vegetable, flower, or just for socializing (…) the planted courtyards survive, adapt to successive modernizations, and function as structuring elements of indigenous urbanism. (…) By arranging green spaces, the new inhabitants transform the landscape designed by architects into a lived landscape.” – as we learn from Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, a book by John Brinckerhoff, that shows how our surroundings reflect our culture.

People get together to be closer to nature. They gather in parks when the weather is nice, arrange gardens around the blocks, grow houseplants, or decorate the stairs of the blocks with ornamental plants. They offer flowers for holidays and onomastici (name days), go on trips to the mountains or the sea, to connect with natural elements. A perpetual search indispensable to life, no matter where we live. People make art with nature and life in mind. In a neighboring village from the capital’s metropolitan area, the Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life was born due to “the shared desires and beliefs of a small community built around love for art, respect for nature, friendship, and mutual trust.” A group of artists, curators, and others co-own and co-manage a plot of land in the village of Siliștea Snagovului and collaborate, based on sustainable, ecological, and ethical principles, in building an “interdisciplinary space for an integrated understanding of culture and nature.” The Research Station aims to become over time “a center for contemporary art and research, a center for the study of nature, and a resource and residency center.” I really liked how they define themselves, because I also believe in the power of the collaboration between art and nature: (the station) “is built around art, because, like nature, art doesn’t exist in itself, but in a network of relations and contaminations; because it preserves memory and opens up the imagination; because art can build communities.”

Ioanid Park / The Journey Ends Under The Moonlight

As a last stop, I invite you to visit Ioanid Park, a small and charming green space with a mysterious atmosphere, very close to the French Institute in Bucharest, Elvire Popesco, where I often go with friends to the cinema. I like to come to the park at night the most, when, like in a dream, this serene place reveals itself to travelers. Street lamps with warm lights, a gazebo, and an artificial lake, right in the middle, unfold like a film set protected by shady branches and, seemingly, with a feng shui precision. We return, thus, to the center, filled with hope and confidence in new possibilities of coexistence and reasons for relaxation and joy.

I like to end articles with a note of optimism. Writing about the green spaces in my city, I was glad to revisit them, but I also faced the feeling that some things could be done much better, that the municipality could take better care of them and its citizens. We need to appreciate what we have, understand where we are, and what the possibilities for change are. We need to believe that things can change for the better. We need gestures of courage that revisit the “relationship with nature.” We need institutions that recognize the ecological and human importance of gardens, parks, and urban forests. At the community level, we need greenery and the life-bringing emotion it expresses. We need solidarity in understanding that only together can things move for the better. We need to preserve what we have and rediscover ourselves in the desire to live in a clean, calm, and green city, which we value and which, in turn, values all of us.