Words: Adriana Sohodoleanu

Photos: Adorjan Trucza

June 2024

I am about to take a leap into the unknown – to an out-of-the-way food festival, in a village an hour away from Miercurea Ciuc, in Harghita County, a mainly Hungarian-speaking region in Eastern Transylvania, Romania. I am a foodie on a quest to understand the Hungarian-managed festival: Taste of Transylvania. A whole weekend alone among strangers, just me and my hunger for taste, stories, and meaning.

I am in the stunning Boros Valley, watching cows grazing on the hill’s slopes from a guesthouse that also serves as a village museum, consisting of 14 old peasant houses, relocated and reconstructed to faithfully preserve their original model. Taste of Transylvania is a gastronomic festival held in autumn dedicated to promoting regional culinary traditions and heritage. The primary sponsor is Budapest’s Hungarian Tourism Agency. I highlight this because its presence and that of others from across the Western border shed a different light on everything, at least in the eyes of some. Given the shifting borders over the last couple of centuries culminating with WWI’s Great Union of Transylvania to the Kingdom of Romania, things are not always simple around here. These counties are sometimes even referred to as Little Hungary. I am also a social scientist, so my culinary journey may take on the nature of fieldwork, focused on complex concepts such as identity and belonging.

In 2022, I learned about the festival late, when it was already in full swing. I was surprised and upset that I hadn’t heard about it earlier. I blamed myself for not being informed and experienced FOMO (fear of missing out). Then, talking to people in the industry, I understood that I didn’t know about it because it wasn’t promoted through traditional channels or general geographic settings – all of Romania – but rather regionally. I felt left out, ignored, discriminated against. I felt like most of the country does when events only happen in big cities: Bucharest, Timișoara, Cluj, or Constanta. I understood and accepted that sometimes those are simply not wanted or needed. However, I still resolved to attend the next edition, to taste Transylvania on its home turf, following the age-old principle of “if you don’t want me, I want you.” Instagram ads had reached my feed announcing early bird tickets but without a line-up or schedule. So, it seemed they wanted us, the Bucharest folks, too. I breathed a sigh of relief and added a ticket to my cart.

Their Way – and Ours

I came here to plunge into the unfamiliar Transylvanian food, or so I thought. It was suggested to me there would be a heavy presence of ethnicity and nationalism. The few pieces of information I gathered beforehand painted a picture away from our national flag’s colors. Sources with expertise in the culinary field told me I would find imaginary borders stronger than the physical ones, a supposed message, and a hidden agenda. Taste of Transylvania, they said, is not about us but about them, the Hungarian community. People close to last year’s attendees emphasized that food is politically charged, a pretext, and a vehicle for more serious matters. So I became curious to observe the mechanisms by which nationalism infuses itself into both cuisine and discourse.

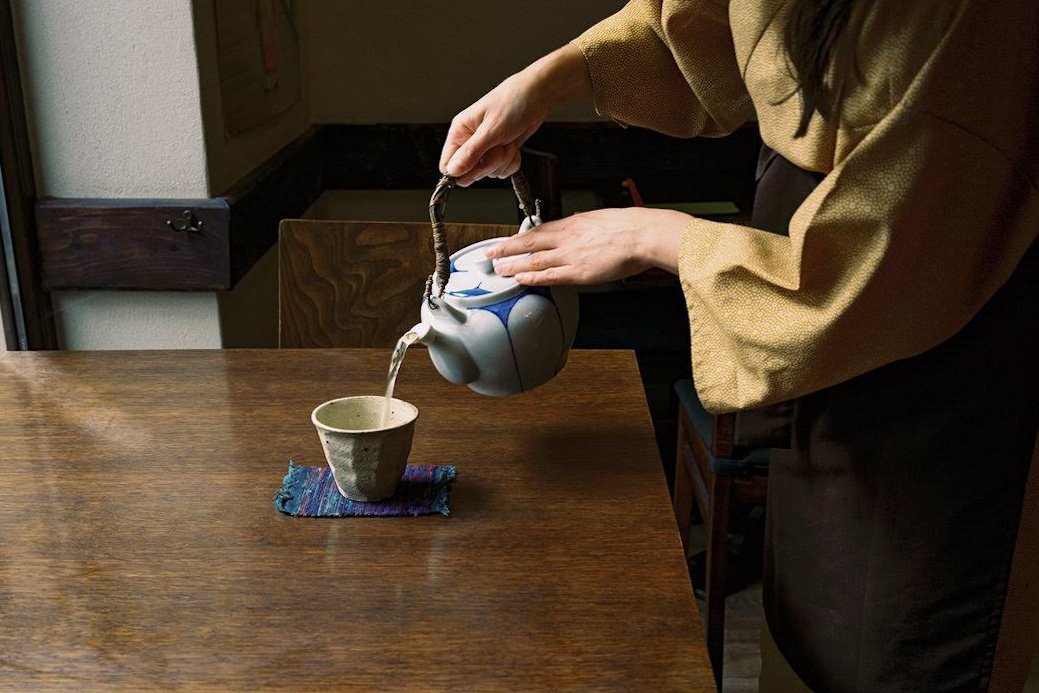

But as I arrived on the scene, I only found myself agreeing with them – sometimes. Hungarian is the only language spoken – most exhibitors are Hungarian, many from Budapest; there’s talk that they came by train, delayed due to a strike. There’s a lot of Mangalica pork (a rare breed of pig of Hungarian origin) on the menu, kürtőskalács sizzling on coals, and beef cheeks cooked with fruit, not tomato sauce, that is their way, not ours. In the evening, the csángók (a sub-group of ethnic Hungarians living in Moldova, a Romanian region neighboring Harghita County) musicians and dancers take to the floor, stomping their feet. I grab a Rigó Jancsi (chocolate mousse) cake with apricot brandy and reflect on my newfound reflex: responding in English when spoken to in Hungarian. It is my brain’s automatic reaction, a solution to a problem. I’ve found out that if Romanian is not spoken, I feel abroad.

Several hands are at work in a nearby pavilion – there are over 10 chefs, each responsible for an element of the final dish. It’s raining steadily now, and visitors have become scarce, comfortably sheltered at the bar or huddled on the porches of the peasant houses. From the corner where the respected Romanian chef Alex Petricean is preparing his mămăligă/polenta quenelles, he is invited to the center to do the plating. The rest gather around him, young men in black tunics with piercing eyes, watching Alex, who is absorbed in his task. When I first met him, his gaze seemed dark. I likened him to a painting hanging in his restaurant of Vlad the Impaler. Now, after watching a Netflix series called The Rise of the Ottomans, the resemblance is even more evident. Alex keeps his head down and his gaze fixed on the plate, like a surgeon in an operation. He also has tweezers. The comparison may raise ironic thoughts; of course, I’m not comparing cooking to surgery, but the concentration, measuring parameters like time and temperature, the precision of the cut, and the finesse of closing an operation are similar. They are attributes of professionalism, skills acquired through years of study and practice.

Alex creates the prototype dish, and a man beside him presents it to the public. The man speaks passionately in Hungarian, while the young chefs nod approvingly, including an older chef, the only one in a white tunic from another era, an influential person when it comes to Hungarian gastronomy. I understand only some French culinary words – beurre blanc, blanchir, and infusion. Alex is not asked anything; he witnesses the presentation with an impenetrable voivode-like demeanor. Later, the Romanian crowd giggled about the fact that they chose Alex to plate the dish, probably to have someone to blame if the preparation didn’t turn out well.

Ethnicity vs. Belonging

When everything is over, and people disperse, licking their plates, I timidly ask if I can have a taste too. But what I’m given is from home; from my mother, from my grandmother, from that Transfăgărășan mountain hut, and even from fine dining restaurants – it embodies everything. Made from cornmeal, beef, dairy, and herbs, it’s essentially mămăligă (polenta) with beef, thymus sauce, and lovage cream. Rich, smoky, salty, and slightly sour, simply delicious. It’s Romanian. But is it truly Romanian? And what does being Romanian mean anyway? Isn’t it more regional or pastoral, perhaps? It’s certainly very subjective, rooted in emotional reminiscence and childhood memories. It’s an expression of the land rather than ethnicity. It’s a sign of respect for the region and its produce. It’s a way to reduce waste and a showcase of contemporary cuisine. It’s evidence of creativity based on strictly local ingredients.

Apart from that, everyone everywhere spoke their language and was understood; the translators were fluent. With or without headphones, Romanians marveled at the deep-fried corn silk; with or without headphones, Hungarians enjoyed Transylvanian chef Oana Coantă ‘s culinary stand-up-like moment. I believe her dish captured the essence of the festival best – ethnicity does not determine belonging. In these parts of the world, people are divided into those who eat their meat with fruits and Bucharest folks (touché). So, what did she cook? A cornmeal pancake with burduf cheese, beef, egg, apple sauce, and pickled beetroot. Romanian? No. Hungarian? No. Transylvanian? Yes. In Romania, just like in Italy or China, we cannot think of food in national terms but rather in regional ones.

I don’t believe the festival proclaimed any irredentist aspirations. I refuse to believe that the lady who chased after me with a plate full to the brim with crispy pork ears and apple sauce wanted to annex anything more than the two pițule (the festival’s currency). And the other lady who came to my table to ask me how the food was didn’t seem like a reiteration of any feudal landlord. The young man selling papricaș with “the dumplings of your life,” pickled cucumbers, and black garlic caviar didn’t ask me for Transylvania. Still, he only wanted two pițule (and yes, they were the dumplings of my life).

Moreover, the audacity of renowned Romanian chef Mihai Toader to come from Bucharest to make (and pronounce) goulash in the land of gulyas did not elicit any disdainful reactions from the audience; in fact, one lady confessed that it was the best she had ever tasted. And when Mihai asked for a brush and received a spatula, the audience whispered helpfully something that Google Translate says was konyhai kefe. Furthermore, the highly Instagramable and educational “Romania on a Plate” dish by Alex Petricean, with its regional divisions and the territorial-gustatory annex called “Basarabia is Romania,” seemed to stir some emotion only in me. People were happy, smiling, and speaking Romanian when they saw you lost; of course, it’s annoying not to know what others are commenting on, not to have someone to gossip with. At most, you could exchange complicit glances, as translators and headsets were at each of the three stages.

Food is Terroir, not Territory

I didn’t see anything to suggest exclusion, national pride, or the promotion of ideas unrelated to food. Everything was about Transylvania and its flavors. The organizers insistently asked the chefs holding cooking demos to only use local ingredients. Instead of flags, there were rows of corn hanging from the porches. Rather than patriotic anthems, there was the sizzle of the grill. There was no parade with paprika, with Mangalica pork, or with slices of Dobos torta (no one mentioned that this famous cake’s recipe is Hungarian, invented in 1884, and registered and protected since 2017 in the Hungarian Food Code, based on a ministerial decree, along with other gastronomic heritages under the name Hungarikum).

The traditional costumes and the people wearing them didn’t give anything away either. Only the broanca, an old local string instrument, caught the attention of those who recognized it, especially Mihai Toader. Sure, pițula might remind you that it was the currency of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918, but who still knows history today, and who looks in the dictionary? Most people I talked to about pițula knew it by that name as a childhood game with beer caps. Personally, I am inclined to see it less as a subversive, discreet move, and more of a commercial interest, given the parity set at 20 lei (4 euros).

I’m glad that my experience in this Hungarian-predominant region turned out to be what I expected – strictly about food and how it brings people together. No matter how ideologically charged this place may be, for me, it was only about its cultural dimension, culinary heritage, and duty.

Without denying or ignoring all the instances where borders have been drawn in dialogue and behavior, without diminishing the weight of certain revisionist longings and aspirations, my experience in Harghita had no political colors, only the taste of the region. True, nationalism can take extreme forms at the dinner table; but Hungarian Mangalica didn’t make any subtle calls for resistance. On the alley called “the way of smoke,” a delicious pig allowed itself to be smoked, sliced, and tasted without discrimination but with sighs of pleasure in the quiet, onomatopoeic language of the world’s food lovers. The same goes for somlói galuska, a sponge cake dessert with vanilla cream and chocolate sauce. And for matured cheeses made by local manufacturer Arkäse in the Swiss Alpine style (this needs explanation, I know — cattle breeders in Harghita and Covasna counties were trained by Swiss cheesemakers as part of a program, they say, allegedly supported by the Hungarian state).

Food from the plate spoke and showed that Transylvania, at least that weekend, was terroir, not territory; an instrument for promoting multiculturalism, not nationalism.