Words: Ioana Negoescu

Illustration: Doina Titanu

May 2024

When Andrei Borțun dreams, he dreams big. So it’s no surprise that when the creative entrepreneur conceptualized a design event in Bucharest, he imagined a grand festival – one that would be “taken over by the city,” embraced and driven by its residents. The dream came true, and the dreaming goes on. Ahead of the 12th edition the Romanian Design Week (RDW), he sees this year’s show as an opportunity not only to bring together the best talents but also to “unlock” the capital’s potential, posing a question to all of us – visitors and creators, locals and foreigners – to reflect on as we marvel at human creativity: what does it take for a city to be truly open? Let’s take a moment to understand how Andrei first asked himself that question, how it led to this year’s theme, and how the festival has evolved since he founded it more than a decade ago.

Since 1998, Andrei has been at the forefront of organizing creative events such as AdPrint Festival, ADOOR, EFFIE, Internetics, and Art Directors Club. Driven by a passion to make an even bigger impact, he envisioned a project that would unite various creative industries, engage with larger communities, and spark real change in our society and economy. Thus, in 2012, RDW was born — a festival designed to unite outstanding designers and architects, in a vibrant, interconnected community ready to innovate and inspire. It revealed the deep need for connection among talented individuals and organizations. From the very first edition, it brought creative minds together, allowing them to share their dreams and challenges. This newfound camaraderie not only transformed how they celebrated their achievements but also empowered them to collaboratively solve problems and push the boundaries of their creativity.

“RDW was initially viewed with much curiosity. Some, already interested and knowledgeable, appreciated that they could see and discover projects and organizations they hadn’t heard of yet, while others looked at what was happening as if it were a UFO,” Andrei tells us.

But what does RDW mean, in short? It is the sum of exhibitions, events, installations, conferences, and parties, all having design (product, graphic, fashion) and architecture as a common denominator. This year’s edition, with the theme Unlock the City, brings more novelties to the public. Besides the RDW Exhibition, which presents the most visionary architecture, design, fashion, and illustration projects, creative minds are promoted through RDW Young Design. For as much relevant international content as possible, the festival showcases some of the most important projects from several European countries through the RDW Design Flags section. Therefore, not only are local initiatives highlighted, but through the RDW Concept Store, visitors can find objects made by both Romanian and international designers. In this edition, the RDW Talks concept, developed last year through a series of podcasts, is now emphasizing face-to-face meetings between the public and visionary creatives from around the world.

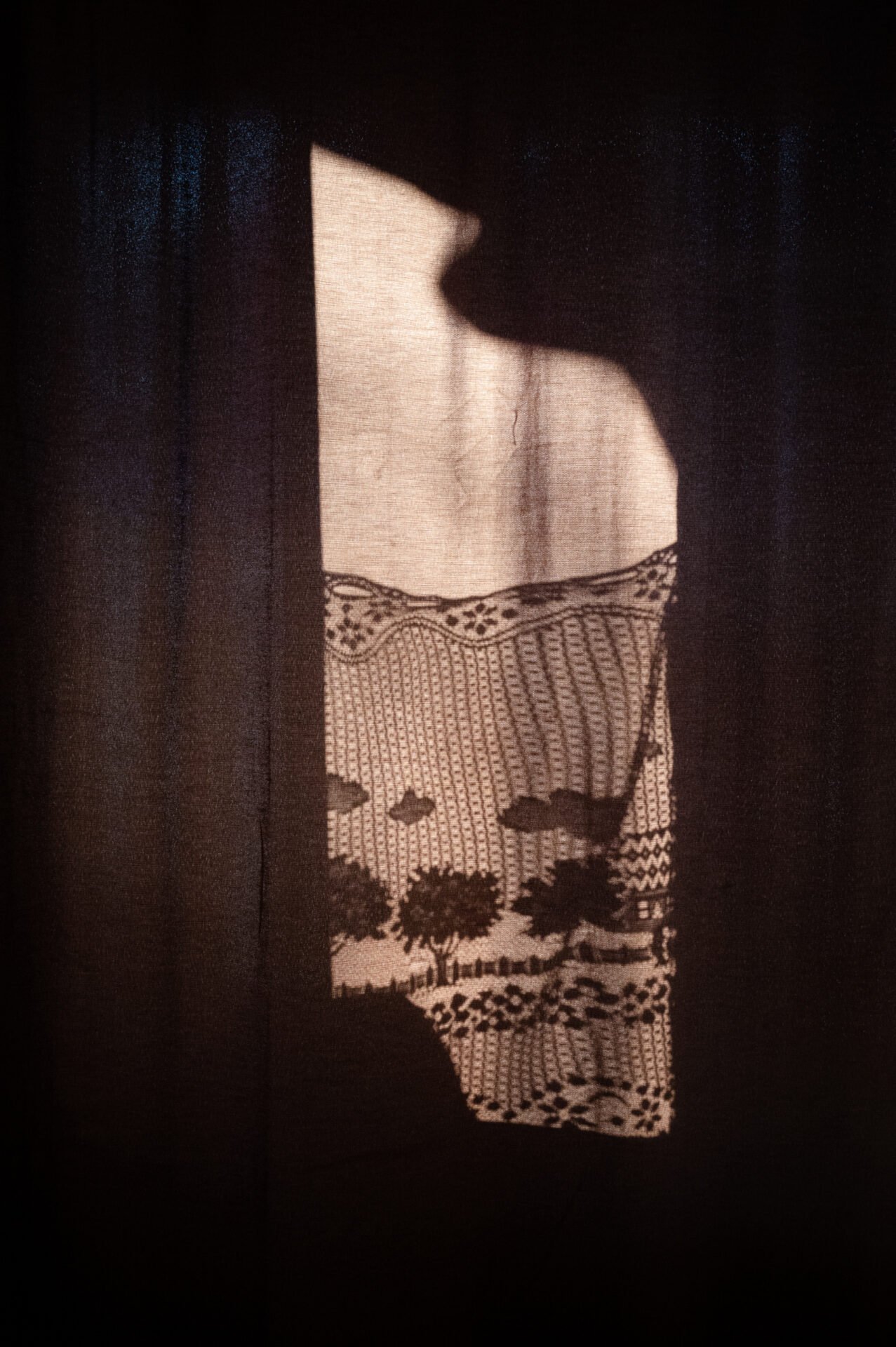

In addition, each building that hosts the festival is carefully selected to reflect the diversity and creative potential of the city. This year it’s the turn of the former CINA restaurant, a symbol of Bucharest, a building constructed in 1907 and now a historical monument. CINA opens the conversation about those places and areas that need to be “unlocked” to bring Bucharest prestige. Probably no other place in the city would have been more suitable for this year’s theme. But then, what does Unlock the City really mean? I spoke to a few festival exhibitors to capture the essence of this edition’s concept, to see what it means to them and how it applies to our beloved city, Bucharest.

Ioana Ciolacu, fashion designer: “The idea that the city is closed and needs to be opened or unlocked is a direction I fully support. To open a city, it takes not only an intention and a plan but also the constant application of this idea. Opening a city means being attentive to the naturalness of the habitat and its residents, customs, dynamics, typologies, but also actively working to raise the standard of living and life.”

Anca Dragu, artist, designer, and founder of the brand Una ca Luna, a ceramic studio: “Unlock the City means activating the creative places in Bucharest. It is a complex event that allows workshops, design studios, architecture, fashion, ceramics, and others to open their doors to the public and interact with them through workshops. The exhibitions, curated by professionals in the field, have been and are followed by both the local and international community. Here, you can see the best new projects in the creative fields. Bucharest thus becomes a city known in Europe for creativity and innovation. As a participant and exhibitor at Romanian Design Week since its early editions, I can say that the festival brings more and more quality creations to the forefront and provides a connection platform between creative fields. ‘Unlocking’ the City makes Bucharest vibrate with creativity.”

Oana Opriș, founder of Genuin – a business with 100% European linen home&deco products: “The Unlock the City concept intrigued us with the idea of co-creating a friendlier city. For us, this year’s theme represents how we imagine Bucharest should be: 1) connected with nature and tradition, because this makes us healthier and more balanced – which is why we use linen in our products; 2) intertwined with modernity while protecting the environment – our reason for upcycling in product design with recycled textiles; 3) full of color and uniqueness – just like Ana Bănică’s illustrations, which we carefully and lovingly embroidered on the pillows we created and will present at the event. We strongly believe that the dialogue, exposure, and creativity of this edition can create meaningful conversations that move the city in the right direction and develop it on multiple layers.”

Andrei Borțun, founder of RDW: “I have always dreamed we would lose control and let people lead the city. That’s how we came to this theme, where we want people to explore the city and become friends with it through design, innovation, and creativity. We contribute to this both by bringing the CINA building back to life and through all the exhibition spaces: Combinatul Fondului Plastic or Piața Amzei being two relevant examples, which are 100% occupied until the end of the year by artists or organizations that otherwise had no place to produce various shows. To open Bucharest, I believe we need to use everything it has that is most beautiful, best, smartest, and most creative. Not to HELP, but to USE. I mean civil society, specialists, cultural institutions, the academic environment, investors, entrepreneurs, etc. To be used, there is a need for objectives, and implementation and monitoring strategies. And beyond budgets, spaces, and facilities, what’s needed is more collaboration between organizations and institutions, and more involvement from the citizens.”

Finally, I asked Andrei what he learned after so many RDW editions: “After 12 editions of the festival, I realized that long-term partners are essential, but you have to offer understanding in return to all those involved in the collaborative relationship, and often it helps to do even more than you promised. I realized how great the need for belonging is among people, whether it’s a large project, a network, a movement, or a group, and at the same time, that the team you are part of must be solid, functional, and built over time. I left the most important thing for last: namely to be flexible and to seek the sustainability of a project rather than the size of the stage or the number of spotlights. Then, don’t forget to ask yourself as often and as honestly as possible why you do certain things, beyond your own reputation or income growth.”

Bucharest has a lot of potential, and events like RDW make it more loved by the inhabitants. This year, for ten days, the city transforms, and everything comes to life through the hundreds of events and activities that take place simultaneously. People explore the streets, going from one location to another, daring to enter the courtyards or inside creative businesses, and discovering forgotten buildings that have been brought back to life.

If you are from Bucharest – or happen to be visiting these days – I invite you to join us in taking over the city and discovering its most creative and exciting offerings. And if you are from another beautiful corner of Romania or the world, then I ask you with much curiosity: what does an open city mean to you?