Words: Lavinia Gogu

Photo: Bogdan Balaceanu

August 2023

Yuki stands as one of Romania’s first Japanese restaurants. This small, family-run operation offers the most genuine Japanese experience in the capital; a relaxed setting with authentic Japanese flavors where everything is created with care and attention to detail. From the Ukiyo-e prints on the walls to the staff’s traditional kimonos and the characteristic aroma of miso, everything at Yuki’s reminded me of a trip I made a few years ago to the Land of the Rising Sun.

While admiring shelves filled with different teacups – which I later learned are individually dedicated to regular clients – I asked about the restaurant’s owner. His name is Yuki Ichiro. I confess that I didn’t expect to find him working in the kitchen. But, as I was to discover, there is nothing conventional about Yuki.

Yuki Ichiro’s professional path is colored with many adventures, bold choices and “a lot of luck,” as he likes to say. It all started in the US three decades ago. After finishing his marketing studies in Oregon, he moved back home to Tokyo, where he spent eight years working in the advertising industry. Life in Japan’s megacity was busy and fun; filled with countless office hours and after work parties – “even when we finished work by 9 or 10 pm!” he remembers. But there were some more travels awaiting him far away from Japan, this time in Europe. The first stop was the Netherlands. Ichiro moved to Rotterdam to enhance his academic experience. He met his now ex-wife there, a woman from Constanța, in south-east Romania, with whom he has two children. The couple moved back to Tokyo where he founded a consulting firm, but they eventually settled in Bucharest. In 2014, in collaboration with Ishii Makoto, a chef and friend from Tokyo, Ichiro opened up the restaurant that bears his name.

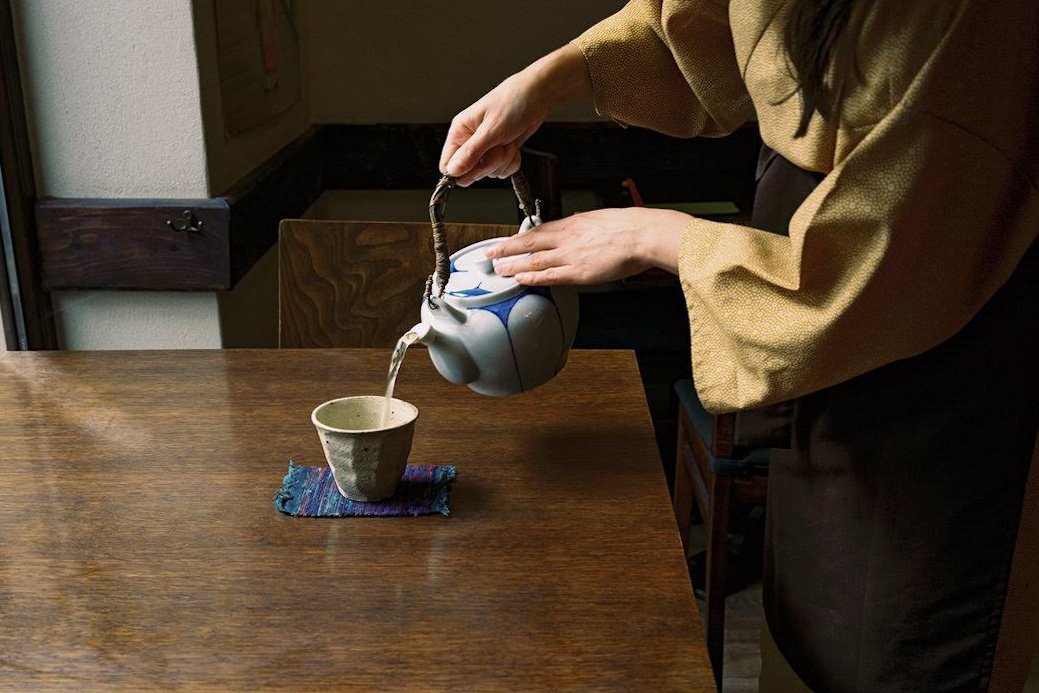

At a table tucked in the back, which also serves him as a working desk – and still wearing an apron – Ichiro pours me herbal tea and tells me his story with a warm, kind voice.

Something that stands out about your background is how well-traveled you are; all the different places where you have lived: from the suburbs of Tokyo to Western and Eastern Europe, via the US. How did your travel journey start?

When I was in high school in Japan, only a few chose to study abroad: the prestigious universities in Tokyo were preferred. I was the only one among my high school friends who decided to study in the US. So I did it – and I began seeing the world and gaining a new perspective. “If you do what everyone else does, you’ll be as good as them at best,” my father told me, encouraging my decision to study abroad. Perhaps his message pushed me to be different and to accept new challenges. He was quite a strict parent. I wouldn’t say we were friends. But I do remember some of his teachings.

After I finished college, I returned to Tokyo and worked for seven or eight years in advertising. But I wanted to see and experience what Europe has to offer. This is how I ended up doing an MBA in the Netherlands, where I met my ex-wife, who introduced me to Romania.

At that time, I was already financially independent and I think I took that step (of studying and living abroad) more out of curiosity. Maybe I was bored with my life in Tokyo. But once I finished my MBA , I was hired by a French company to open a subsidiary in Japan and ended up being one of its founders. So I moved back to Tokyo with my ex-wife and lived there for nine years.

I didn’t doubt my choices in life – I didn’t question my destiny. In Tokyo, everyone worked extremely hard and I never had a problem with working overtime or on weekends. We worked a lot, but we also had fun. I would go out to party after work, even when we finished at 8, 9 or 10 pm!

So, what brought you to Romania?

In 2011, after an earthquake, tsunami and then radiation, we decided to come to Romania. These unfortunate events were the triggers.

Before that, I would visit Romania once a year, for a week or two, for my children to see their grandparents at the seaside. The idea of moving to Romania was mine, a decision I processed for nine years. I actually think I had this idea planted in me all along, since my very first visit here.

My ex-wife was more skeptical about the move because she loved Japan and had learned the language. She didn’t think it was the right time: it was too early. We decided to live in Bucharest and not Constanța because there is a Japanese school here, in Pipera. Our eldest son was in primary school and the youngest in kindergarten. It took some time to get things in order in Japan and prepare for the move, but I did it with pleasure.

I can say that I have always considered myself lucky in life. And this brings me to another thing that my father told me. He was an entrepreneur, and even if he could delegate, he preferred interviewing each employee personally. He always asked candidates if they considered themselves lucky, and wouldn’t hire them if they said no. I think I’m lucky.

What were the first culture shocks you had when you visited Romania?

My first impression of Bucharest was that the city is gloomy. The buildings and even the people seemed gray, starting with their choice of clothing to their facial expressions. And I don’t mean it negatively; I’m just comparing it to how it looks today. In fact, I knew from my wife that Romanians are very friendly and open-hearted people, once you get to know them.

But I can’t say that I was surprised by anything. I was already used to culture shocks.

What do you like the most about living in Bucharest?

Romanian traditions are beautiful. What captivated me the most was the slow pace of life. Tokyo has a quick and exciting pace. Everything works flawlessly, as expected. But every time I came here, I was fascinated by the leisurely life of the locals and I dreamed of it: a good balance between personal and professional life. Family orientation is a Romanian inclination that I really appreciate.

There are many advantages of living in Romania. Expats who are restaurant customers always tell me that they are delighted with the friendly people, the city’s safety (Bucharest is considered one of the safest European capitals) and the reasonable cost of living.

Now that I have lived here for 10 years, I realize some problems with the educational and medical systems exist. I now understand my ex-wife’s reservations because these factors are also very important in the quality of life. The quality of the services in the stores and the relationship with the authorities and governmental institutions can also leave something to be desired. But that’s another story. Life is good here in Bucharest.

How do you like to spend your free time in Bucharest?

I like the parks in the city. I also enjoy Romanian films: the stories are authentic and I appreciate the actors’ performances. I have over a dozen DVDs with old movies, but I watch current Romanian movies too, both in cinemas and on Netflix. Currently, my favorite Romanian films are “A fost sau n-a fost” (12:08 East of Bucharest) and “Anul Pierdut 1986” (Clouds of Chernobyl), which I recently saw in cinemas.

But if I have more time at my disposal, I prefer to travel around the country. I love the countryside, where I have discovered so much beauty, for the eye and spirit.

When I explored Transylvania and Bucovina, I met many foreigners. Veteran travelers know just how lovely it is here. They often come from Western Europe and always seem to know where to go and what to do. There is something precious here. I love the small villages, Criț and Viscri in Transylvania. I always bring my friends from Japan to visit and they are delighted. These places have a special beauty and sense of authenticity.

Is there something you dislike about living here?

I don’t like that, in general terms, the authorities are unwilling to help you much. Maybe it’s not a surprise for others, but where I come from, town halls, for example, are there to serve you as a citizen. This is reflected in how they are organized. For example: someone explained to me that the main entrance of the City Hall of District 1 is for the mayor and for the most important people, while the citizens have to go through a small door at the back. In contrast, in Japan, public service is really public service; officials are there to serve the citizens. The citizens enter through the main entrance while the staff enter through the back.

In addition, corruption is still part of the Romanian system, although the situation is improving. Many people are intrigued by the fact that it still doesn’t seem normal to me. I am often asked why I’m not happy that money can solve problems. But things are improving year by year.

What are the major differences for you between Romanian and Japanese societies?

There are many differences in the education systems. In Japan, schools prepare children for life: they teach them to become members of society and train them to work well in a team. But by living here and observing my children’s education, which has a Romanian component, I observe that they are unprepared for teamwork.

The Romanian education system focuses on the subjects of study and encourages competition. For example, exam results are displayed from the highest to the lowest grade, with first and last names. In Japan, exam results aren’t displayed at all. My parents never asked me about my grades, much less compared to other kids. Another difference is that, in Japan, students have a lot of extracurricular activities. The year is filled with events, and the kids have assigned responsibilities at each event.

In addition, schools in Japan have committees with a wide variety of subjects, ranging from animal committees to flower committees and such. These are held regularly and push students to make decisions according to their roles. It simulates society on a micro level. These school organizations have hierarchies. The older students are the leaders while the younger ones are the apprentices, so they learn from their seniors. This system is implemented from a very young age, sometimes even at kindergarten, to inspire mutual respect and trust. This system is continued throughout the Japanese work environment. Every time you start a new job, you start from scratch. You become an apprentice all over again. In Romania, I noticed a different mentality; that your boss is allowed to exacerbate his/her power over you, while in Japan, the approach is that the leader takes care of his or her subordinates. By the time a young Japanese man reaches adulthood, he has been through this hierarchy system three or four times. He is ready and knows how to integrate into the team, respect his peers and lead.

Considering these cultural differences, how do you relate to the Romanian staff in your restaurant?

They are talkative and I enjoy working with them, but they are unprepared for teamwork. It can sometimes be quite difficult for me. It may be difficult for you to imagine, but in Japanese culture, when you join an organization, you will work in several departments for the first two years, regardless of what college you graduated from. This is the training period where you must understand what everyone does to form a holistic view of the company. This philosophy is also applied in services, sometimes with great success.

For example, if a chef has the time to serve the client, he does. This is because they can better explain the dishes, ingredients and preparation methods. I don’t think many restaurants do this here, but I try this multipurpose method because I think it makes sense, especially in a small team. But I often hear: “I’m a chef, I don’t wash dishes.” Things don’t work that way in the Japanese system.

So is this why I caught you working in the kitchen when I got to the restaurant?

Yes, I make desserts, I help in the kitchen for an hour or two, I even patrol the street in front of the restaurant. And this creates funny reactions because people get worried and sometimes even ask me why I am cleaning the street. But that’s teamwork. And I think this mentality is hard to implement after the age of 25, when people are already trained. Perhaps this is one of the biggest challenges of running a business here as a Japanese person.

What lessons from Japanese culture and from your father would you like to pass on to your children – and which ones from Romanian culture?

I retained a formula for success from my father which I interpreted like this: result or reward = talent (from 1 to 10) x effort (from 0 to almost infinity) x luck (1 or 0).

And speaking of effort: a strong sense of purpose and resilience to hard work have always been values found in my father’s words which are also fundamental to Japanese society. Japanese schools focus on compassion and empathy more than competition between students. Teamwork requires compassion, and compassion requires mutual respect and trust.

What about luck? Well, reality hurts, because we are not lucky all the time. One thing we could do is to continue to make an effort – that is, to be alert, so that we are more likely to take advantage of opportunities when they arise.

However, no one can continue to work hard all their lives. We need breaks. The question is when to work hard and when to rest, and we’d better find out the answer that works for us earlier in life rather than later. But the painful reality is that we do not have an answer until we work hard. Only in adulthood can we be wise enough to discuss these decisions in terms of life stages.

Japanese culture teaches us to work hard because rest comes after significant effort. But here in Romania I am learning a completely different approach. One that helps me find balance on my own terms.

How is the balance between personal and professional life now, in this unpredictable post-pandemic socio-economic climate and with a war so close?

First of all, I am lucky to be in Romania, both as a freedom-loving individual and as a hospitality entrepreneur during the pandemic. The regulations were not as strict as in most other countries in Europe and our business survived.

Now, as in many other restaurants everywhere, clients are coming back to enjoy their social life, probably even more than before, while many customers have become accustomed to eating food delivered at home, unfortunately.

How has the Asian cuisine scene in Bucharest changed in recent years?

Over the last seven and a half years since I opened the restaurant, a lot has changed. Several restaurants with this profile have opened and the quality has improved, but of course, when it comes to Japanese cuisine, Romania is still in its infancy. Here, when you think of a Japanese restaurant, people tend to automatically think of sushi.

In other parts of the world this association is changing. In Western Europe and the US, Japanese food is no longer perceived as just sushi, but also as ramen and many other things. Every market goes through the same stages. We noticed this in the US 30 years ago, then in the Netherlands 20 years ago.

Which kind of Japanese food do you serve in your restaurant?

Ishii Makoto, the chef with whom I launched the venture, is not a sushi chef: he specialized in traditional Japanese dishes. He is originally from Tokyo and has worked in the food service industry for over 20 years.

In Japan, sushi is not an everyday food, and I don’t know any Japanese person who eats sushi daily. Rather, we eat them on occasions. When I lived in Tokyo, I would eat out maybe once a month, and we would occasionally go to a restaurant with friends to enjoy the talent of a specialized chef.

Yuki is a restaurant that serves authentic Japanese food in a city that focuses more on sushi – how does it work?

Our restaurant in Bucharest works well even if we don’t serve sushi because Romanians naturally favor what is good. Several foreigners have expressed this observation to me. I’m used to quality ingredients and the vegetables taste amazing here. Even my mother, who visited Romania twice, mentioned that the ingredients here taste better.

Of course, if you go to the supermarket, you can find products imported from Holland, Turkey or Greece, but Romanians know how to identify the natural taste of food. And that’s exactly what we try to offer at our restaurant: food with genuine, natural taste. We do not use flavor enhancers or chemicals of any kind. Romanians can identify this difference and appreciate it.

Which dishes from Yuki’s menu would you recommend to someone only familiar with sushi from Japanese cuisine?

We practice slow cooking, which is why we have a small menu, so I think it is important for our guests to try them all.