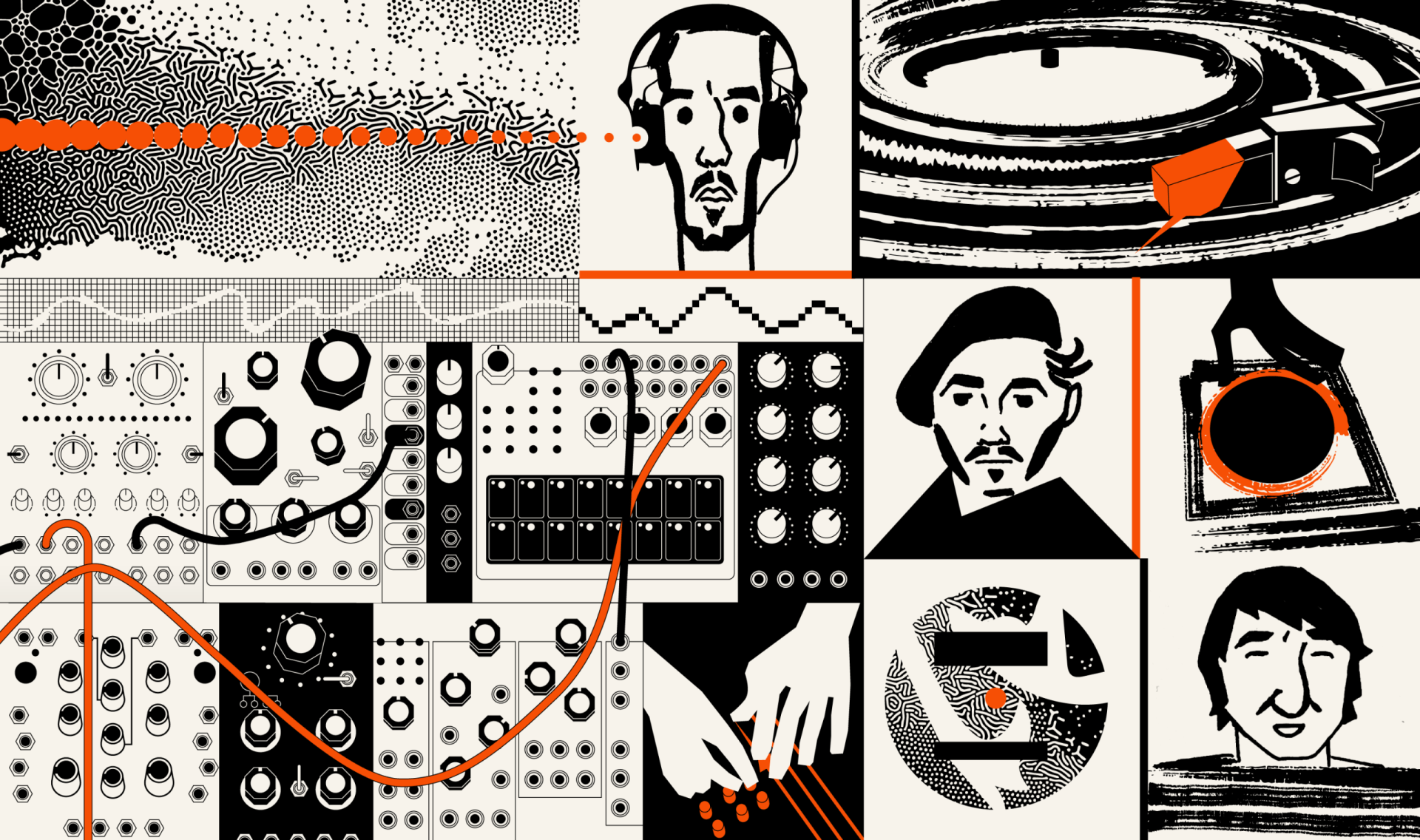

Words: Dragoș Rusu

Illustration: Sorina Vazelina

September 2024

Explaining what Romanian minimal means today, even within the context of electronic dance music, can be challenging. Although it emerged as an underground cultural movement, the term has gained enormous global traction over the past two decades.

On the one hand, Romanian minimal (or rominimal) is a subgenre of electronic dance music born within the Romanian scene, which has seen remarkable worldwide expansion. On the other hand, the concept has lost its original meaning over the years and no longer accurately reflects any aesthetic reality. Paradoxically, it is criticized and denounced even by those who were once considered pioneers of this movement. “When I hear about Romanian minimal, I feel like hanging myself from a chandelier,” Radu Bodiu, a Romanian DJ and producer known by the name Petre Inspirescu (formerly Pedro), told me in 2019. Rolling like a snowball across countries and continents, rominimal has now become a phenomenon that defies Western taxonomies, ultimately achieving the status of a national brand.

Aesthetically, until just a few years ago, the term ‘rominimal’ could be vaguely defined as a blend of microhouse, tech-house, deep house, minimal techno, and minimal house (due to the lack of more precise categorizations). However, for almost a decade now, subgenres and genres have begun to merge and intermingle at a much faster pace, and Rominimal has become a worn-out tag, struggling for self-representation. But like any myth, this one too has its own story. To better understand what’s going on with Romanian minimal, a bit of historical context is needed.

Romanian Clubbing After the Revolution

Like many post-socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, Romania underwent a rapid series of cultural transformations following the 1989 revolution. After the end of communist propaganda, censorship, and prohibitions of all kinds, and the opening of Western borders, the Romanian cultural landscape became stratified. As class differences became increasingly visible, Romanian society began to embrace Western pop culture values.

In this amalgamation of fast changes and Western aspirations, a new electronic music scene quietly emerged. Influenced by what was being broadcast on TV, particularly channels like Viva, MTV, and Atomic TV, the Romanian electronic music scene of the late ’90s arose as a cultural need of a young generation for a unique identity and a desire to explore a completely new musical landscape.

For someone like me who started going to parties in the early 2000s, when clubbing began to attract more and more curious souls, memories of now-defunct clubs in Bucharest (like Studio Martin, Web Club, Kristal in Floreasca, Session, or La Mania and Motor in Mamaia), will surely evoke a wave of nostalgia. These were some of the first places where one could see and listen to live DJs performances and experience the institutionalization of the local club culture. The dynamics, social classes, and hierarchies of the future Romanian electronic scene gradually took shape, evolving with each new artist who set foot in a Romanian club for the first time.

This cultural expansion was made possible primarily thanks to key individuals (promoters and artists) who laid the groundwork for the scene.

The First Promoters and the Birth of Sunwaves Festival

Romania never had a heyday of rave culture. The few raves that took place in different alternative spaces in Bucharest were held in an extremely private setting. And in the absence of a rave ethos, the club and the culture scene was seen – in capitalist terms – as a mere new market; one that grows and develops, has an audience, and, at some point, has the potential to reach its peak – or fail and be forgotten. Since there wasn’t much room for sonic experimentation in general, and almost everyone stuck to safe recipes, party and festival offerings were usually coming from two entities – The Mission and Sunrise – very different in terms of values, structure, and music approach.

In the early 2000s, besides the clubs that were open every weekend, new promoters began to organize events in alternative spaces (like Preoteasa in Bucharest). At the same time, more established brands like The Mission and later Sunrise, expanded their reach, hosting larger-scale events that extended beyond the club sphere, attracting more and more participants. This resulted in DJ-led events in huge venues in Bucharest –such as Arenele Romane, Romexpo, and World Trade Plaza – and also various festivals at the seaside in Mamaia.

The most long-standing and successful of them all was (and still is) Sunwaves. Starting from 2007, an increasing number of foreigners started to come to Romania for the newly established festival, which has since become a biannual event and is the longest-running electronic music festival in Romania. As of September 2024, it reached its 33rd edition, expanding to Roquetas de Mar, Almeria, Spain. Over time, the festival has grown so much that it now serves as an international gathering point for thousands of participants hailing from all corners of the globe. Moreover, in addition to its headquarters in the Mamaia and Olimp resorts on the Romanian coast, the Sunwaves festival has expanded abroad in recent years, hosting special editions in Zanzibar and Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates.

On a personal note, my first Sunwaves experience was its second edition in 2007, and my most recent one was the 26th edition in 2019, when I had the joy of playing music on one of the stages. During all this time, I’ve witnessed with my own eyes the magnitude of the festival, which had become almost a city in itself. Everything grew so much, diversified, and accelerated so fast that it is undeniable today that this festival stands as one of Romania’s most successful international tourist brands.

But the electronic music scene in Romania was buzzing with activity beyond just the festival scene. Coming back to the city events, new entities emerged. Although Bucharest remained the busiest city in terms of club events for a while, in time, parties with DJs started to take place in other cities across the country, like Iași (XS club), Craiova (Krypton club), Timișoara (No Name club and the TM Base dnb festival), Cluj-Napoca (Midi club), Bacău (Zebra club), Galați (Club Pasha) or Târgu-Mureș (Avicola club).

The Mission managed a part of Romanian DJs, and was in charge of the Studio Martin program, as well as organizing big events at Arenele Romane and on the seaside. Meanwhile, Sunrise introduced a more underground and less commercial alternative, experimenting with new subgenres of electronic music, including the first visits to Romania of Richie Hawtin, Magda, Troy Pierce, and Ricardo Villalobos. While The Mission brand was always seen as a profitable business, and their events with trance and progressive house music targeted the widest possible audience, Sunrise underwent a period of experimentation with more or less successful experiments. This included a series of events at Motor club in Mamaia and later at Session club in Bucharest. These first attempts grew along with the sound they promoted, namely a segment of Richie Hawtin’s M_Nus record label, focused on minimal techno and minimal house during that time.

Raresh the wonder kid and the [a:rpia:r] Soundsystem

Sunrise started as a booking agency in 2000 and later evolved into a brand for organizing events. In an interview from 2008, Sunrise manager, Cătălin Ghinea aka Tati, told me that Romanian DJs “needed representation.” Since there was a growing demand in the country for DJs from Bucharest, and Sunrise already had their well-established contacts, they became a kind of DJ boutique in a relatively short time. “In practice, until the summer of 2007, you could only get DJs through Sunrise, or you couldn’t get them anywhere else.”

The agency grew along with the [a:rpia:r] project – initiated by Cătălin together with Rhadoo, Petre Inspirescu, and Raresh – a project that over time became one of the most profitable businesses for any promoter and large club manager worldwide, as Ghinea confessed. Their own productions contributed to this hype, as well as their attitude behind the decks. The combination of successful parties, exclusive vinyl-only releases in limited quantities to boost demand, and international distribution all added to its allure.

Raresh always received constant support from Sunrise, and he was one of the first artists that Cătălin Ghinea believed in right from the very start when Raresh was just 14-15 years old. When Raresh decided to move with his family from Bacău to Bucharest, his path was already becoming clearer, but the turning point in his career was the event with Ricardo Villalobos at Studio Martin in early 2006. Ghinea remembers it well: “After that weekend, Ricardo Villalobos sent me a message and told me he was still shocked by how good Raresh was. People weren’t really used back then to foreign artists DJing after 3 AM, but Ricardo kept telling me ‘Let him play for another 20 minutes, let him play two more tracks!'” This led to a private after-party where Ricardo and Raresh played back-to-back for 18 or 19 hours. A few months later, Raresh signed with Sven Vath’s Cocoon booking agency, and international gigs started to come. As for the [a:rpia:r] Soundsystem, fast forward a decade later, a major turn in their career was the Circoloco residency at the DC10 club in Ibiza, which paved the way for other artists from Sunrise to play on the island. All this eventually led to a strong and globally praised music connection between Ibiza and Bucharest.

Meanwhile, things have evolved tremendously, and everything now happens on a much more advanced scale, thanks to a solid infrastructure built over years and which includes artists (namely DJs and producers), record labels (with vinyl releases and global distribution) and a wide network of contacts from all around the world. This growth has had a big impact on the sound itself, with that minimal effect being visibly diminished and transformed into something else. But it’s not just the sound that has changed; society and its clubbing policies have also evolved as older generations have grown up, making room for younger ones.

In the past decade, more and more new entities have emerged on the Romanian music scene: Guesthouse club, the deep/beach scene from the Waha festival (which has now ended its journey after its 10th edition), the Ourown booking agency, dozens of record labels, an impressive wave of DJs and producers constantly releasing records, a solid relationship with international distributors, plus a bunch of new promoters organizing events all over the country. All of these factors have made a fundamental contribution to the scene’s structure and have created fusions that have radically transformed the sound.

Present and Future Prospects

Sharing a similar fate with tech-house, rominimal has been in danger of implosion for several years. Trying to define it today is like looking at a freight train with an infinite number of wagons, with no discernible locomotive. As a metaphor inspired by sociological theories of world systems that assume the division of the world into core countries (the most developed ones – the center), semi-peripheral (in process of development) countries, and peripheral (underdeveloped) countries, we can also imagine the rominimal scene being divided into three main regions, which would reflect not only various ways of production specific for each region, but also the degree of development itself of each region. Although the dynamics among them are complex, and the struggle for hegemony is fought over resources, the center will always dominate the periphery, constantly reinforcing a co-dependent relationship.

If we take a look at what has been happening in recent years in the scene, we can observe a tendency of the center distancing itself from the term ‘Romanian minimal’—a tag contested also by the first generations of party goers from Bucharest. Nevertheless, while still attractive to foreign tourists, it is possible that entities positioned in the semi-periphery may still use this label for self-representation and conceptualization. Perhaps this ambivalence surrounding Rominimal is a debatable matter of taste, what we can clearly observe here is a very well-structured business model, where hierarchies are visible, and everyone knows their role within this performing arts ecosystem.