Words & Photos: Andrea Dimofte

April 2024

Have you ever wondered how it feels to be blind? How would you react if you were told you’d gradually, but surely, lose your sight? What would you need in order to navigate the world around you? Perhaps you’ve closed your eyes for a while and focused on your other senses while trying to go about your typical day – certainly atypical for most, but a reality for many. There are currently over 40 million blind people in the world, each with different degrees of impairments, – and Cornel Amariei has taken on the task of helping them. He is the CEO of tech startup dotLumen, a company he founded in 2020 in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, through which he has designed an innovative device – “glasses for the blind” as he calls them – to improve the mobility of people with visual disabilities worldwide.

Today, even with all the advancements in technology, only a few solutions can substantially aid a blind person. The Braille alphabet has been of help to pass on information for over a hundred years. Most smartphones and computers have a text-to-speech system, which converts written text into spoken words. But when it comes to mobility, walking around the house or on the street – something most of us often take for granted – there are only two solutions: the walking cane and the guide dog. Cornel and his team have embraced the challenge of bringing a new solution to the table.

Born in Bucharest, Cornel spent part of his childhood in Campul Lung Moldovenesc, in Bucovina, northern Romania. He learned to program at the age of 7. At 15, he founded Romania’s first high-school Robotics Club. During his teenage years, he also launched two companies, one of which paid for his higher education in Germany at Jacobs University. Now, at 30, he manages a team of 50 people dedicated to empowering the blind through assistive technology. His company is Romania’s first startup to get funding from the European Innovation Council. And while his products have not hit the market yet, research and development are well underway.

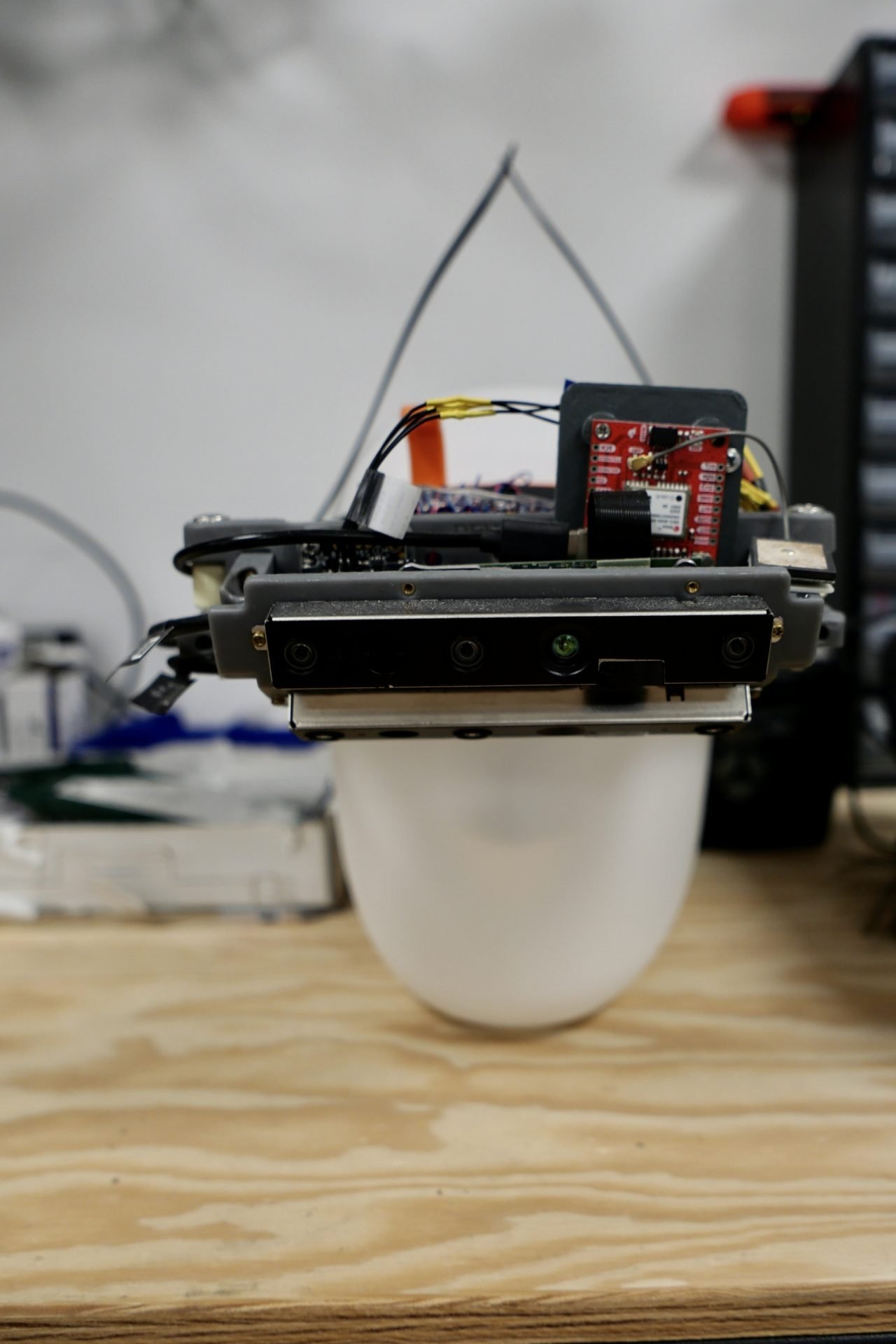

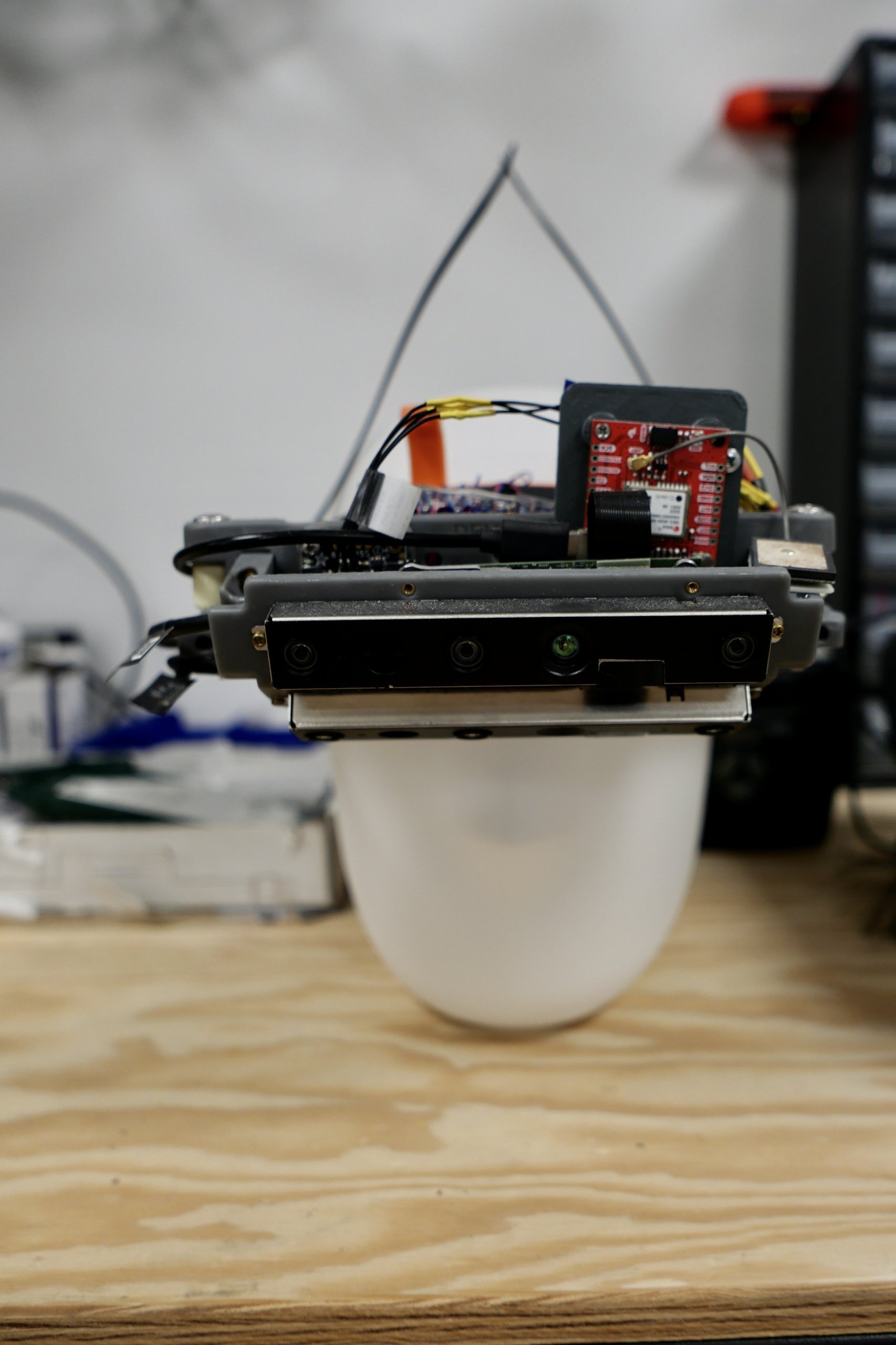

I recently visited their offices, scattered over three floors, filled with gadgets and testing rooms, to learn more about their ambitious project. But to my surprise, we didn’t just talk. I spent much of the day blindfolded, trying to succeed at the many tasks Cornel and his team gave me. At first, I had to guess different shapes on papers before me. I then got acquainted with the white cane. I stumbled around their building, trying to make my way out of the elevator and onto the street. I was then ready to try on a prototype of their glasses. Still blindfolded, I carefully placed the device around my forehead. It was lighter than I expected. And then, off I went. The device is equipped with multiple cameras that constantly analyze the external surroundings. With the help of haptic and auditory feedback, it guided me through the neighborhood by generating pinching sensations on my forehead. Indeed, it helped me avoid obstacles coming my way – such as cars or children playing ball – nudging me to take safer routes. By the end of the walk, I was speechless. As we sat down for lunch in one of Cluj’s charming little restaurants, I was ready to pick Cornel’s brain for this interview.

You are very young to have started such an ambitious project; tell us a bit about yourself.

Both of my parents have locomotive disabilities, and my sister, who is 16 years older than me, has a severe mental disability. It was a challenging environment for me to grow up in. Due to my sister’s emotional instability, the energy at home was often tense. We also had limited financial means. But, as I grew up, I noticed how much technology can help. I began a career in locomotives and became the head of innovation at Continental Automotive Systems, one of the world’s largest automotive manufacturers. I worked on their electronics and autonomous driving, initially in Romania, then in Germany, and with many international teams. I got to travel quite a bit and met many interesting people.

So where does the dotLumen story begin?

I often found myself surrounded by people with disabilities. When I began my career in tech about three and a half years ago, I thought of merging the two. With George, a childhood friend from Bucovina who worked with me at Continental Automotive Systems, we started researching mobility solutions for people with visual disabilities. And well, we couldn’t really find any. The guide dog and the cane have existed for decades but have limitations. Training a guide dog can be extremely expensive, and caring for them is a big responsibility too. On top of that, they’re a scarce resource. While there are 40 million blind people around the world — a number expected to increase drastically — and nearly 300 million people suffering from low vision, we have estimated just around 30,000 active guide dogs.

Since we come from an autonomous driving background and understand how to make cars drive themselves, we thought: ‘why not try to replicate the main features of a guide dog through technology?’

What are the main differences on how a cane, a guide dog, and your glasses can assist visually impaired people?

The white cane simply extends your perception. You will only feel an obstacle up to the length of your cane. But the cane won’t tell you how to go around the obstacle – it will simply inform you there is one. A guide dog, or a human companion for that matter, would guide you. They understand the situation you find yourself in and create a path plan. The dog pulls your hand or makes you stop at a crosswalk. Our glasses take this to the next level. For instance, with the help of the internet and GPS, they can bring you to places you’ve never been before, while the guide dog can’t do that. Our glasses can also speak to you and inform you about your environment – giving you a more rounded experience. And while your dog needs maintenance, our glasses only require to be charged.

People also don’t talk about the training conditions guide dogs go through to do their job right. They are purposely bred and born in a particular setting. They start training when they are only 6 days old and never fully experience a more normal canine life.

What is the technology behind the glasses?

From a technological standpoint, the self-driving car is the most comparable product. While self-driving cars determine the direction to take on roads, our glasses do that on sidewalks, and they must first understand their environment. They discern where the ground is and identify obstacles, which are the first thing the device determines, geometrically. But they go beyond that. For instance, the trajectory might still be unsafe even if you have a flat surface in front of you with no obstacles; a road could be perfectly flat but have cars driving on it – making it unsafe. Similarly, a perfectly flat lake would not be recognizable as dangerous by a delivery robot. Our glasses can examine each surface individually, taking in all these factors to determine whether the person can safely walk.

They also determine distance. They contain six cameras, four of which are used for stereoscopic view, which help determine distance. They also have many sensors, such as gyroscopes and GPS sensors. They determine the distance between your movements. Then, with all that information, path plans are quickly created and sent back through feedback mechanisms – the vibrations you feel on your forehead.

What were some of the technical challenges you encountered?

One of the major ones was that there was never a system hardware that had the computing power for what we required: to have something as small as this to compute everything it had to compute. It was a huge challenge to design a machine-learning model that could do what we needed.

The aim is for the glasses to be versatile – to help people in as many different settings as possible. Some of the technical challenges arise from the region we test in, which is why collecting data from different parts of the world is essential. For instance, in Eastern Europe, parking cars on the side of the road is common. That isn’t the case in most of Western Europe. We struggled to teach the device that cars can be parked on the side of the road without causing danger. We also struggled to make the device work in both humid temperatures and below zero degrees Celsius.

There was also the forehead challenge: we wanted the glasses to fit everyone. It’s as if we had to design a one-size-fits-all pair of shoes. The device had to be comfortable on your forehead. We had to study anthropometry and head shapes. We made hundreds of forehead scans to figure out how to shape the device. We now have nearly 500 – the world’s most extensive forehead study. We have the world’s largest forehead study because we have the only one. There are simply so many different shapes: some are round, some are flat, some are smaller at the top, or more prominent at the top. We didn’t want the devices to be tailor-made since that’s not scalable.

Did you interact a lot with people with visual disabilities even before starting the project?

Yes, definitely. Due to the family I was raised in, I was exposed to all types of disabilities from a young age, ranging from mental, locomotive, hearing, speaking, and, of course, visual. When you have a disability, I noticed that communities get formed, which is always helpful and wonderful. So that’s how I got to meet more people.

Which other insights did you gain by working with the blind?

I learned that it’s all about those small things that improve a person’s quality of life. We conducted hundreds of hours of interviews with blind people, to get a better understanding of the types of problems that arise in their day-to-day lives. We wanted to learn how they cook and eat. How they experience Netflix. How they determine the direction of a bedroom. We discovered that they travel much more than we would have thought – less than visually capable people, but they do travel. Each aspect of what we consider ‘normal behavior’ for us as visually capable individuals is different for a person with a visual disability. Everything from personal hygiene to how they choose their clothes. For instance, they often ask visually capable people their opinions when selecting clothes to know if colors match.

What is a blind person’s relationship with color?

Well, a person with a visual disability can still perceive light. There are many degrees of visual impairments and many people who experience them can still perceive color. But for those who are blind, color is a concept they understand theoretically, not in practice. They also attach color to emotions – for instance, they know that red is associated with warmth and blue with sadness. I had a conversation once with someone blind about green shoes and asked her whether she preferred them light or dark green, and I could sense that while she understood the concept of the color, she struggled with its nuances.

Tell us about some technology that already exists to help the blind.

There are many apps designed to help a blind person in various aspects. Some of them can determine colors and suggest combinations. There is a lot of technology that can assist the blind with daily tasks. For instance, washing machines have easy accessibility features, where each button makes a particular sound. Things like that. Many people with disabilities are early adopters of technologies – it enables them to do more things. There’s this famous saying from one of IBM’s directors: “Technology makes things easier for people without disabilities. But for people with disabilities, technology makes things possible.”

How would you weigh technology’s importance in daily life vs a person’s mental well-being?

Determination and resilience are key to doing the things you set out to do. While we strive to offer mobility independence, people can have all the technology in the world, but without will and a healthy state of mind, they won’t be able to function in society, and the technology will be useless. A person’s mental health is extremely important.

So, how should we help someone with visual disabilities?

The most straightforward advice I can give is to first ask if they want help in the first place. Then, ask how. Most people with visual disabilities would be able to describe what they need. Then I’d say – just don’t be weird about it. People with disabilities want to be treated as normally as possible and as typically as possible.

I think it is a shame that mainstream schools don’t teach those without disabilities how to help those with disabilities. I have noticed that people generally are well-intentioned and want to help, but simply don’t know how to.

DotLumen has become an award-winning startup. What are some of the awards, and how do you feel about them?

Indeed, we have won multiple awards since we launched the company. We won the Red Dot: Luminary award in 2021 for design – the nominees included the Virgin Galactic Spaceship interior by Seymourpowell, the world’s first commercial spaceship. We also won the MedTech award in 2023, an event dubbed as Germany’s technology ‘Oscars.’ And we were selected as finalists for the New European Bauhaus Prize in 2023 out of over 1,450 applicants.

Sometimes, I get overwhelmed with imposter syndrome. But other times, these awards and recognition empower me and my team, making us more ambitious. We get a boost in productivity because we want to feel like we deserve these awards. On a practical level, they also help us with international visibility, allowing us to get the attention of large companies.

We hope that if more people and companies learn about our mission, we can accelerate our efforts to finally start helping visually impaired people.