Words: Lavinia Gogu & Andrea Dimofte

Photos: Bogdan Balaceanu

August 2023

Their interest in wolves brought them together, but their love for Romania’s abundant forests – and for each other – pushed Christoph and Barbara Promberger to build one of Europe’s largest conservation projects. Christoph Promberger always had a passion for nature conservation. After finishing his master’s thesis on wolf behavior in the Yukon Territory, Canada, the German biologist started The Carpathian Large Carnivore Project (CLCP) in Romania in 1993. It was the first project to study the behavior of Carpathian wolves and other large carnivores in the area, such as bears and lynxes. Barbara Fuerpass joined the team a few years later. She was captivated by Romania’s wilderness of the 1990s, but later also saddened by the abusive deforestation.

Romania has Europe’s largest continuous forest region, covering over six million hectares, possibly up to 500,000 hectares still virgin or at least in a close-to-original state. The Carpathian Mountains are home to the country’s most diverse mix of wildlife, hosting over 3,500 animal species. Christoph and Barbara outlined an ambitious conservation plan: to protect the Făgăraș Mountains area, part of the Carpathian Mountains in southern Transylvania and northern Walachia, by turning it into Europe’s largest forest national park – what they fondly refer to as the “European Yellowstone.” The couple founded Foundation Conservation Carpathia (FCC) in 2009 to prevent deforestation and create the world-class wildlife reserve that protects and allows biodiversity to thrive.

They began buying land in 2007. They aim to acquire 35,000 hectares to stop unsustainable logging and abusive exploration practices, and support ecological and wildlife restoration. The areas they bought include the Natura 2000 site in the Făgăraș Mountains and the Piatra Craiului National Park, thus provoking additional 200,000 hectares to be fully protected. In 1996, after Piatra Craiului was designated national park, the government restituted parts of it to private individuals, consequently leading to trees being cut down. That is why Christoph and Barbara could buy land, too. Following the model of other international conservative philanthropists, they intend to eventually donate the land to the state for management, with a solid and respected legal framework, to guarantee the ecosystem’s and wildlife’s preservation for future generations. They believe that a national park must belong to the nation.

In addition to acquiring land, FCC has a lot of conservation projects underway. They replant trees in areas affected by deforestation and focus on rewilding, having reintroduced bison and beavers into their natural habitat. Their next step is to bring the vultures back to the Romanian forests. They also have strong initiatives to support local communities by establishing sustainable economic opportunities. They create jobs and educational projects while encouraging conscious tourism.

Though they have been facing many challenges, Barbara and Christoph are well underway to transform their conservation initiatives into realities together with local communities. After Romania joined the EU in 2007, they could access European funds. With the country’s general economic recovery, the population’s appreciation for nature is changing. Today, many Romanians are proud of their native forests, home to the most significant European large carnivore population and one of Europe’s most important biodiversity hotspots. The younger generation, especially, is becoming more in tune with the importance of environmental protection.

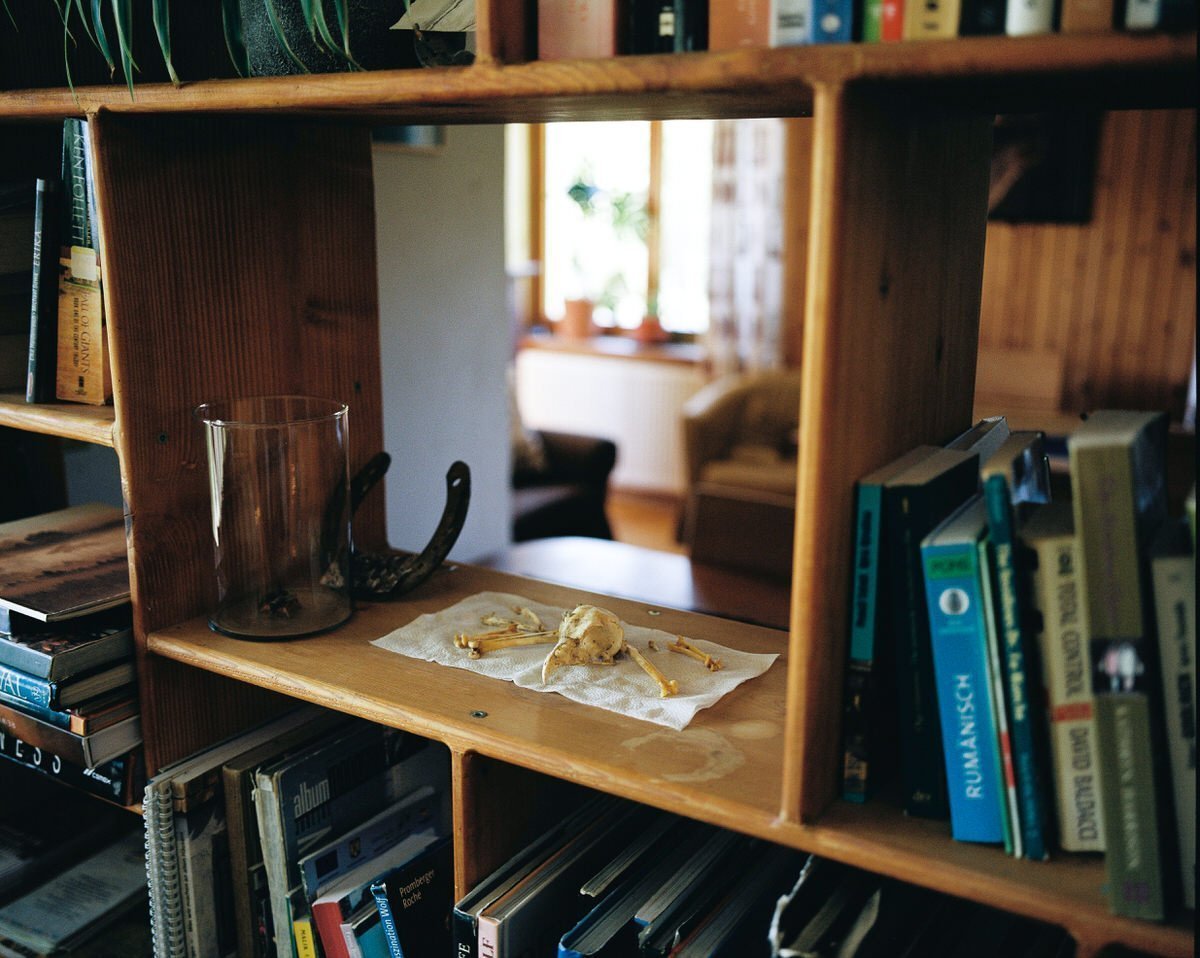

After a few days of hiking together, we spoke to Christoph and Barbara in their bohemian-decorated living room at their Equus Silvania Equestrian Center, the guest house they completed in the early 2000s, near the little village of Șinca Nouă. The space was filled with books dedicated to wildlife, a piano with romantic song sheet music, and pampered cats roaming around, nesting on our laps as we spoke. As their energy filled the room, we couldn’t wait to dive deeper into their story: to better understand how the German man and the Austrian woman devoted their life to conserving Romanian forests.

What was your first contact with Romania?

Christoph: I was doing my master’s thesis on wolves in Yukon, the northwest corner of Canada. They are amazing animals and I love them, so I decided to study their relationship with ravens. I was curious; the Natives of the Yukon know there is a deep relation between the two species and many researchers reported anecdotal observations of them spending a lot of time together during winter. When I returned to Europe to write up my findings, I wondered what to do next. I wanted to continue working with wolves, and in the early 90s, the Iron Curtain had just fallen, so Eastern Europe had become accessible. The West had more money and know-how but there were more wolves in the East. Italy had 150, Sweden 100, Portugal 300… while Romania had 3,000. Luckily, I got to know someone who worked at the Forest Research Institute in Brașov and we created a team to explore the Carpathian Mountains. That’s how I first got to Romania in 1993. We started out small, but over the years more staff and volunteers joined the team, and I decided to stay more than just a few years.

Barbara: I grew up in a rural area in Austria: I always loved spending time in the country, in nature – for me, city life would have been a tragedy. And although I didn’t grow up on a farm, I always had a close relationship with animals. So, it became obvious to me that I would be a veterinarian. But as a teenager, I realized that this profession is not about animals as much as it is about their owners. I was very disillusioned. At that time, I was reading quite a lot about the science of animal behavior, and I realized that that was the path I wanted to follow in life, so I ended up studying biology in Vienna. I wanted to work with wild animals, not sit in a lab. And like Christoph, I wanted to know more about wolves. Naturally, I headed to North America and the Yukon, Canada.

Christoph also worked in that area in Canada, is that where you met?

Barbara: No. Someone I met in the Yukon recommended that I meet Christoph, since he was working with wolves in Europe. He gave me his address and phone number. It’s a long story because all the information I received was wrong, and this was before the internet, so I couldn’t find him on Facebook. I eventually found out his place of work in Germany. When I finally reached him, I realized he was Bavarian by dialect, and imagined him working with captive wolves in the Bavarian Forest National Park. But luckily, he was working with the wild wolves and told me they needed someone right away. When the conversation ended, I realized I had forgotten to ask where I was supposed to go. In fact, that very same day I received an acceptance letter for a project in Poland that I had applied to. But I was more intrigued by what Christoph had told me.

I called Christoph again and found out that it was Romania. At the time, all I knew about Romania were Ceaușescu, the orphanages and, of course, the Carpathians. I will never forget it: Christoph said that Romania is shaped like a lemon, and that right in the middle is Brașov. I arrived in Brașov a week later. It was late, dark, and people seemed reserved. But the first days I discovered the area, the surrounding villages were wonderful. At the time, I didn’t speak the language and the locals didn’t understand German, but somehow, I could understand them. I first fell in love with the country, and then with Christoph.

Christoph: It happened over time. Barbara and I worked as a team for several years before we got together. But once we did, in 1997, we married just a year later. Sometimes you just know.

You both say you loved Romania right away. What fascinated you the most about it?

Christoph: I think the wildness of the country, as it was in the 90s. But also the wildness of the people, and I say that in a positive way. People were so connected to their environment! Of course, there were some negative aspects – like the killing of wolf cubs – but Romanian people were authentic and untainted by the western way of life. Growing up, I spent a lot of time in the Bavarian forests, but when I first arrived here and saw the woods, bears, wolves, and lynxes, I understood what a forest is: beyond nature, it’s an ecosystem. When I returned to Germany, the over-managed forests there seemed soulless.

Barbara: Things were not so regulated in Romania in the ‘90s. I appreciated that a lot because there was a lot of common sense. Sometimes, a life without rules can be chaotic. But it can also allow certain freedoms and creative ideas to arise, new concepts in segments still untapped in the country at the time. We liked the idea of a real fresh start.

Why did you decide to stay here?

Christoph: We completed the Large Carnivore Project in 2003. We had an offer to go to Scotland together to work in conservation. But when we visited, we found a gloomy landscape. A local told us that we were lucky to have a beautiful day. “It’s the first day in half a year when it doesn’t rain,” he said. I prefer a snowy winter to a rainy one. In addition, I had become very attached to Romania; it gives me a sense of belonging. I realized that Romania had become home when I was visiting Germany. Back in Romania, we wanted to open an equestrian center to develop equestrian tourism because Barbara loves horses. We were very naive about what it means to open a guest house, but in 2004 we opened the center. It was exciting but intense, since we also had two small children. We did almost everything by ourselves. We took care of the horses and the kids while cooking and trying to make money as well. We worked on international projects too.

How did you create the Foundation Conservation Carpathia (FCC) and what is its mission?

Christoph: I went to the Piatra Craiului National Park in 2006 to print a large map. I spoke by chance to the director of the park, who told me that with the restitution of forests to people, who owned them before they were nationalized during communism, people started to cut trees without anyone stopping them – since everyone, from the forester to the authorities, was bribed. It was shocking and frustrating because we had been involved with the research project there, and national parks are supposed to exist to protect nature. With the fall of communism in 1989, the government privatized many of its formerly nationalized forests. The National Forestry Directorate distributed protected park lands to private individuals, who could do whatever they wanted with them. Many just wanted to make money, selling them off to logging companies. Soon everyone in the area got involved: from the police to the forest guard. Thus, the timber mafia was born.

Trying to find solutions, I spoke to the park director who said: “The only solution is to find someone who would buy these forests and protect them.” We laughed together, as we thought that wouldn’t happen. But a few weeks later we found a Swiss donor who decided to get involved. That’s how we got the first funds and started the foundation to save the Piatra Craiului National Park. This was before we set our eyes on the Făgăraș Mountains, which have the potential to become the largest national park in Europe, the “European Yellowstone.”

Barbara: In fact, the vision to create a national park in the Făgăraș Mountains took shape over time. Since everything started as a land acquisition project for conservation purposes, we did not communicate our project to not influence land prices. But when we also began buying deforested areas, we had other challenges. For example, forest laws require replanting to occur two years after deforestation. And then, we realized that the land we bought needed to be protected from illegal logging, so we raised funds to finance forest guards. That’s how we started communicating the project.

How have you been perceived by the local community and what challenges have you encountered?

Christoph: The name I got from the people in the area is “Neamțu,” meaning “the German” in Romanian. I even appeared that way in newspaper headlines, so we will probably always be considered foreigners, even if we live here for the rest of our lives. But we get along well with the community. People appreciate the fact that we learned the language and that we promote the country. However, our nationality was also used as propaganda by the timber mafia. We were demonized, accused of stealing resources and selling the country. People who didn’t know us were inclined to believe that was true.

Barbara: When I told the public that our purpose is to buy land to protect it, some even suspected we had found gold. The idea that our goal was purely philanthropic was dubious to many Romanians since these kinds of projects are not common practice here.

How do you involve Romanians in FCC projects?

Barbara: We have a volunteer program, and although we’ve often been told we don’t have enough Romanian volunteers, this is quickly changing. The younger Romanian generation now believes that it is an activity that benefits their personal development. From the CVs we currently receive, we can tell that many people have experience in volunteering. Our team now has 130 people who are all passionate about the cause, even though it is a challenging job, whether you are working as a security guard, planting trees, or organizing events.

Which of your conservation projects do you think will have the most substantial impact on the future of Romania?

Barbara: We are still buying land, but we will probably stop at some point. We will protect the forests and find ways to compensate individual forest owners for conservation, rather than deforestation. We will continue to reforest degraded landscapes, to complete the missing links in the ecosystem – we started with the reintroduction of bison and beavers into the wild. The reintroduction of vultures is the next step. They became extinct due to killing and poisoning; people poisoned wolves, and when the vultures consumed their carcasses, they, too, died from poisoning. Back then, people considered wolves, not bears, the main enemy because they attacked flocks.

What is the most pressing conservation issue: deforestation or illegal hunting?

Barbara: Deforestation is more problematic because it has a much longer impact: if you cut down a forest, it won’t recover for the next 120 years. Although it needs to be controlled, hunting doesn’t damage the ecosystem as much as habitat loss. Many animal populations regenerate faster than the forest.

Christoph: I’m not as relaxed about hunting. The functions of an ecosystem depend on wild animals.

What do you think about the supposed country’s bear overpopulation problem?

Barbara: Nobody has any proof of the claimed growing bear population. We see many on social media and on the side of the streets, but what do we see? Public opinion is influenced by the media, so it has become a topic of debate. Hunters are upset because trophy hunting has become illegal, so they are incentivized to show how bears are causing more trouble. I have lived in Romania for 25 years and know that these things have happened before. Every year, people get killed by bears. But back in the day, it was usually just a small mention on a newspaper corner. People used to be afraid of wolves much more than they are of bears now.

Christoph: We’re not saying there aren’t more bears – we are saying that we don’t know, and nobody knows. We do believe that bears have started showing up in areas where they weren’t seen in the last 20-30 years.

Barbara: Also, the habit of going into the forest didn’t exist before. Now people go hiking and mountain biking – so of course, more bears are seen.

You have studied the behavior of wild animals in the Carpathians for ten years; what should be our reaction if we meet a bear?

Christoph: There are two situations in which bears can be dangerous. When you catch a female bear with cubs, she may attack you to protect her cubs. The second case, which can easily be found in many parts of Romania, like in Sinaia, Predeal, Băile Tușnad, Transfăgărășan and others, is when bears fed by tourists have lost their fear of us. Also, once they associate humans with food, all is good if they get it. But if they are not fed, any factor can cause them to become aggressive.

Barbara: That’s why people must keep their trash out of reach. For now, the government seems to be only trying to find a solution to legalize trophy hunting to reduce the bear population, but luckily, they are constrained by European legislation. I am convinced that even if half of the bears disappeared, the situation would not change much. Trophy hunters will not shoot the cubs, but will instead target large bears, which are more impressive on the wall. We need to make sure that garbage is not accessible to bears, that there are patrols to scare them, and that they are not fed by people. These methods are used all over the world. Ultimately, a fed bear is a dead bear.

Why and when do you intend to donate the land purchased through FCC to the State?

Barbara: When we founded the FCC, we emphasized that the land would not belong to the foundation forever, but that it would be returned to Romanians, provided that the area is protected. The government will have to offer a very concise way to manage and finance the national park in the future.

Christoph: Douglas Tompkins, a famous conservationist and philanthropist, said: “By definition, a national park must belong to the nation.” I followed his example. He bought a million hectares in Patagonia, South America, to create several national parks, and then offered the land to the state on the condition that it manage it and eventually add territory to the preserved area. That is what we intend to do.

Have you always been environmentalists? What is your lifestyle now?

Barbara: I think we are lifelong learners. I remember in college I wasn’t aware of all the consequences of my actions. I learned many things later. But when it comes to nature preservation, I learned from my parents. They taught me how to recycle. How to not be wasteful in any regard. We try to offer a completely vegetarian menu when we put together events or conferences. If we offer meat, we make sure we know its source.

Christoph: But our lives and jobs have quite a large carbon footprint. This year we’ve already had many flights for foundation purposes, which of course, is a disaster. So I can’t point the finger at anyone because we’re not perfect. But I am aware and try to tip the balance as much as possible through small, constant actions. If I can change something for the better, I do. We use a Dutch company that makes phones with materials from areas where child exploitation is prohibited. They do not use resources from war zones, everything is recycled, and any component of the phone can be changed/repaired: for example, if my camera is broken, I can replace it. There are thousand such examples, and the more we follow, the better it is.

When you become aware of the consequences of your actions and the importance of preserving nature, you start to question every decision you make.